The Douglas County Poor Farm

By Brian Hall

The poor house was a social institution that dates back to 1697 when the first English workhouse opened in Bristol, England. The poor house came along due to parameters set by Queen Elizabeth I in 1601 which called for taxes to be collected and the creation of almshouses for the aged, infirmed, mothers of illegitimate children and children incapable of work. It was important legislation because it established state responsibility for the poor and began a standard by which care should be delivered.

The English law followed colonists to America and the first public almshouse in America was started in Philadelphia in 1731. All residents—lame, sick, vagrants, aged, children, unmarried mothers, blind and able-bodied poor—were housed together and worked for their keep. In Midwestern states, the almshouses were typically called “poor farms” and it was run as exactly that. Male residents tended animals and crops and performed routine maintenance. Women took care of the house and household chores.

The first poor farms in Kansas were started in Leavenworth and Douglas Counties in 1866. By 1899, eighty of the 105 counties had poor farms. The poor farm in Douglas County was first organized in 1866 when the county commission minutes showed a purchase of a 160-acre farm from George Sterns for $2,200.

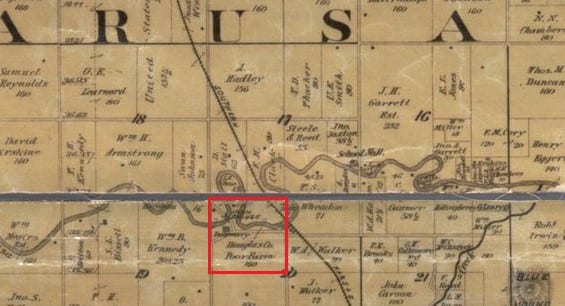

The 160 acres was located one and one quarter mile south of 31st Street and Haskell Avenue on the south side of the Wakarusa River. The legal boundaries of the property were the northwest quarter of Township 13, Range 20 and Section 20 and according to a 1857 map of Douglas County, the property was owned by R.P. Moore at some point the property came under the ownership of George Sterns.

1857 plat map of Douglas County. R.P. Moore property highlighted in red.

The county purchased the land January 30, 1866 and four days later plans for a farmhouse “two stories high, 24 feet wide by 36 feet long to be built on the county farm and used for a county asylum for the poor” were noted. The farmhouse cost $3,760. No pictures of this farmhouse exist but at the time, the poor farm houses looked like your typical farmhouses from that period. In March, a superintendent was hired for the cost of $1,200 a year for himself and his family.

Census records from 1870 list twelve residents of the farm. Two males were listed as “farm laborers” and a woman was “keeping house.” Six ‘paupers,’ ranging from 2-year-old Willy to an 80-year-old man, were listed as illiterate, and one was designated an ‘idiot.’ People on the farm worked if they were able to. They maintained the house, tended crops, fed livestock—which mainly consisted from cows, pigs and chickens—and women usually did housework including cooking, cleaning and laundry.

In 1887, the Poor Farm’s superintendent was a Mr. Dodge who was described by some as a “common drunkard” and “a profane and brutal man.” When an aged Irishman died at the farm and was buried unceremoniously in the farm cemetery on the bank of the Wakarusa River, George Hollingberry expressed his unhappiness with the neglect and mistreatment of the county home to the Lawrence Daily Journal and county commissioners. While several people testified that Mr. Dodge was a good farmer, they still felt he should be removed as superintendent of “The Home.”

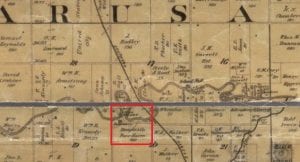

1887 Douglas County map showing Poor Farm property in red. This also shows the road leading south from Lawrence and bearing east across the Wakarusa River and ending at a T-intersection.

In the early 1900s, Daniel F. Heaston was the superintendent of the Poor Farm. The Heastons originally owned a farm two and a half miles south of Pleasant Grove. They were a very religious family and held devotionals every evening before retiring to bed. The Heastons remained the farm superintendents until shortly after the new building was opened when they moved to Lawrence and operated a broom shop.

A list of names recorded by the poor farm and submitted to the Douglas County commission shows that the poor farm assisted 109 people between 1909 and 1910 and this was in addition to the people whose residence was at the farm. Most of the patrons were from Lawrence but Lecompton, Eudora and Baldwin City were represented as were Lone Star, Lecompton Township and Vinland.

One of the more interesting names on the list is a Mrs. Mary Henderson who doesn’t have an address listed next to her but “Cocain Mary.” From newspaper archives, “Cocaine Mary” was an interesting character in Lawrence. Mentions of her in the various newspapers report her many arrests due to drugs and drunkenness. In 1910, she was shot at a party in Bloomington but it was unclear whether someone shot her or she shot herself. After accosting people heading to the Santa Fe Depot at 7th and New Jersey Streets, Mary was arrested and put on trial to determine if she should be remanded to the custody of the county. She was declared unfit to care for herself but, having no relatives and being unable to find anyone to take up the burden, she was released back into society. She is listed as being arrested again with a “Mexican friend whose name can’t be written” for indecent conduct. After that incident, news on “Cocaine Mary” ceased.

Deciding that it was time to expand the poor farm, county commissioners accepted the construction bid from John H. Petty of $22,944.00 to construct a two-story, brick structure with large pillars in front. Commissioners formally accepted the building on March 13, 1911 finding it “according to contract in every respect.” The old frame house was torn down.

The 1911 Douglas County Poor Farm. People in front are unidentified.

The early 1910s was a good time for Lawrence. The city had more paved streets than any other Kansas city and the new building exceeded the expectations of a poor farm. Residents seemed to enjoy living there and it was the county commission that made the farm pay for itself. “I can remember it very distinctly,” County Commissioner Bob Neis said. “When I was a kid we used to go out there and buy some seeds or cows or pigs.” But Neis also noted that “it was a black eye in somebody’s life to end up at the poor farm.”

On March 15, 1927, a barn was destroyed by fire. W.J. Welshimer had been dismissed from the farm earlier that day and was later convicted of arson in the fourth degree. When he appeared for sentence at the jail, he stated “you wouldn’t keep me at the County Home, so I had to fix it so you would keep me some place.”

Aside from the occasional news report, life at the poor farm was quiet and peaceful. The farm provided most of its own food and raised livestock but tragedy struck in the early morning hours of April 11, 1944.

Superintendent George Hoskinson was awakened by the screams of two elderly men in the basement. George rushed to fight the flames while his wife went to a nearby farm to call the fire department. By the time the fire department arrived, flames had already engulfed the building. Hoskinson and six other employees were able to rescue the 26 residents. Eight residents burned to death in the fire. Mr. Hoskinson said that he helped one inmate out twice but she returned to the building and died in the flames. Another man, 69-years-old, was taken to Lawrence Memorial Hospital with both legs fractured having either fell or jumped from a second story window.

The fire could clearly be seen from Lawrence and later that day, Coroner C.B. Ramsey assembled a jury to visit the ruins of the home to gather evidence and to remove the remains of the deceased. With the help of the Red Cross, inmates were cared for at the Community Building at 11th & Vermont Streets until arrangements could be made for their care. Fire Chief Paul Ingels surmised that the fire started in a fusebox. County Commissioners also announced the next day that a small farmhouse would be built southwest of the poor farm ruins using salvageable material from the gutted building. The county sold the livestock and equipment and finally the land in 1946.

The 1944 farmhouse on the Poor Farm land. Photo by Dale Nimz for the Kansas Historical Resource Inventory.

World War II affected the commissioners decision to abandon the poor farm but still wanting and needing to care for the elderly, the county quickly bought a house at 1004 West 4th Street to be used as a convalescent hospital.

Lucius H. Perkins was born in Racine County, Wisconsin on March 5, 1855. His parents, natives of Onondaga County, New York, were among the pioneers of southeastern Wisconsin. Perkins ancestry appeared as early as the tenth century and possessed large estates surrounding Ufton Court in Berkshire. The first Perkins to come to America was John W. who arrived in 1631 aboard the Lion and became a member of the Massachusetts Bay Colony at Ipswich. He later moved to Norwich, Connecticut where they remained for nearly 200 years when they moved to New York.

In 1877, Lucius graduated from Beloit College and moved to Lawrence where he became a student of law in the office of Judge Solon O. Thacher. After two years, he became a member of the first graduating class of the University of Kansas School of Law. He was one of the first to be appointed on the State Board of Law Examiners and retained that position until his death.

On May 15, 1882, Mr. Perkins married Clara Morris. They had four children, Bertram (1883-1887), Clement (1885-1966), Rollin (1889-1993) and Lucius J. (1897-2003). Mr. Perkins was fond of travel, devotedly attached to his home, loved the companionship of his fellow men and opened his home, a stately house he named Ufton Court, after his ancestral home in Berkshire, designed by John G. Haskell, 25 rooms, three-stories with a red tile roof and decorative tower, for all the neighboring boys. Mr. Perkins died suddenly at his home on June 1, 1907 from a fall at his house.

After Perkins’ death, the house was sold to the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity. During World War II, the house was renamed Victory Mansion and was a home for employees of the Sunflower Ordnance Plant in DeSoto. The county bought the house the day after the fire and in September of that year, the Douglas County Convalescent Hospital opened with 31 beds. Through the years numerous additions would be added on but the building had problems.

“It wasn’t what you would call a safe place for old people,” Douglas County Commissioner Walter Kampschroder remembered. “[T]he state health department got to checking and […] they were putting quite a bit of heat on us,” he said. On November 4, 1958, voters narrowly approved the construction of a new county nursing home. Two years later, voters approved the sale of the old home which was purchased by the Medical Arts Center and razed in 1962 for a parking lot.

The Valleyview Care Home opened in April 1961 at 2518 Ridge Court with 51 beds. The county leased the home to private operators and paid a monthly fee for all county partners. In 1975, commissioners were urged to return as the operators of the home since “maintaining […] profit was the prime concern of […] private operators.” The county took charge of the home the remainder of the time it was open.

The Valley View Care Home. Today, the building houses the United Way along with numerous other charitable agencies.

In 1992, the Valley View board of trustees voted to turn over management to Retirement Management, Inc. when Valley View became too much of a financial drain for the county. RMI then decided to build a new facility to replace Valley View near its Brandon Woods facility near 15th Street and Wakarusa Drive. Valley View officially closed its doors September 1, 1995 effectively ending Douglas County’s 129-year history assisting the sick and elderly.

In 1996, the United Way of Douglas County purchased the building to use as their offices along with the offices of numerous other charities such as the Red Cross, Girl Scouts, Big Brothers Big Sisters and Tenant to Homeowner. The Poor Farm is marked today by a barn and silo on the south side of North 1175 Road, a chicken coop and root cellar.

The Poor Farm Cemetery and Deaths

The Douglas County Poor Farm Cemetery was “situated on the banks of the Wakarusa River in a narrow strip of land between the river and the road”, was supposedly unmarked and used throughout the years as a cow pasture where the land was desecrated by rooting pigs and the tramp of horses and cows. The exact location of the cemetery is unknown and it’s suggested that it no longer exists due to the change in the Wakarusa River’s channel.

The only cemetery records for the poor farm exist in mortuary records from C.W. Smith. It shows only the burials that C.W. Smith Mortuary handled for the poor farm. Known burials in the Poor Farm Cemetery are:

Joseph Franklin, buried Dec. 16, 1893, aged 64

Infant Furgason, buried Jan. 4, 1891, no age given

Child Hattan, buried Apr. 28, 1893, no age given

Infant Edwards, buried Nov. 25, 1901, stillborn

Minnie Anderson, buried Jan. 19, 1894, no age given

Daniel Barkley, buried Jan. 23, 1895, no age given

Mrs. Lowe, buried Oct. 21, 1891, no age given

Carrie Low(s), buried January 1893

Unknown Sukey, buried Feb. 11, 1891

Unknown Jackson, buried July 3, 1892

Child of Carder, buried Apr. 22, 1893

Ora Wright, buried May 10, 1892

Eight people died in the Poor Farm fire of April 13, 1944. Listed are those who died in the fire, their age, residence and location of burial:

Mrs. Albert Bebout, 86, Lawrence, buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, Lawrence

Mrs. Ida Clark, 80, Lecompton, buried in Maple Grove Cemetery, Lecompton

Miss Elizabeth Whitelaw, 76, Topeka, buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, Lawrence

Peter Luzius, 83, Lawrence, buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, Lawrence

Fred W. Plateman, 88, Big Springs, possibly buried in Stull Cemetery, Stull

William St. Clair, 88, Big Springs, Maple Grove Cemetery, Lecompton

Isaac Tabor, 71, Lawrence, burial currently unknown

Lafayette Tabor, 82, Lawrence, buried in Beulah Cemetery, Colby

Blog post courtesy of Brian Hall. Brian has a summer interpreter position with the Lecompton Historical Society, funded by the Douglas County Heritage Office and by Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area. Brian Hall has lived in Lawrence, Baldwin City, and now Topeka. He works for Topeka Public Schools, is a writer and amateur historian.